When Helen and I decided to get married, we wanted to create an event that was fulfilling and exciting for everyone involved. We also had a lot of people in our friend group who were approaching transition points in their lives, and we wanted to create an atmosphere that enabled people to focus on their own long-term commitments. Finally, we wanted to create something that helped bring our community closer together.

We are the sort of people who will happily ignore tradition if it suits us, but we also wanted to understand historical origins of various wedding traditions as well as different cultures’ approaches to celebrating long-term commitments. Blind rejection is as much of a mistake as blind acceptance!

What truly matters:

We started our event planning by making a list of what mattered the most to us.

First, we wanted to ensure that there was ample time for the sort of deep connection-building we were looking for. Most weddings in my experience are about 6 hours long, and if there are 100 guests, this means you’ll get an average of 3.6 minutes with each guest. Practically speaking, it’s even lower because you’ll be occupied with the ceremony, dinner, and various structured activities for at least half of the time. This means some people might fly across the country to see you and still barely get a word in with you. I believe part of this problem is that the wedding-industrial complex has pushed people’s expectations of the level of fanciness of a wedding to be particularly high, and most people simply can’t afford to offer several days of celebration at the prices charged by wedding venues and caterers.

Second, we wanted to ensure that our community could use the event to continue to bond together. In our past experience with Burning Man camps and various large parties, we’ve found co-creation to be one of the most powerful methods of bonding. This co-creation can be anything from art to food to music to seminars to event logistics. For this event, we encouraged everyone to become a participant in making the event happen, whether in planned or unplanned ways. There’s a certain shift that happens when everyone feels responsible for making something go well — it’s a mix of trust and mutual gratitude that emerges.

Finally, we wanted to create an atmosphere of reflection on our commitments. However, these commitments weren’t just to each other. They were to ourselves, our community, and the world. We felt these other commitments were as important and as much worth highlighting as our commitments to one another. We chose to theme the event around the act of setting intentions and making commitments, and everything from the art to the workshops to the Journey — a guided group meditation and ritual — was designed to reflect that. This also enabled others to focus on their commitments as well.

The setting:

We chose a site along the beautiful Mendocino coast that could comfortably sleep about 30 people in a farmhouse and cabins and had additional room for another 100+ people to camp or visit. There were also a lot of airbnbs nearby. This mix of accommodations allowed us to accommodate a large group of people with widely varying incomes and needs. The overall property was 39 acres and connected to a beautiful but little-used beach, forest, and rocky coastline full of trails. This gave us a whole estate to inhabit for a few days, and enough room for people to both gather and spread out.

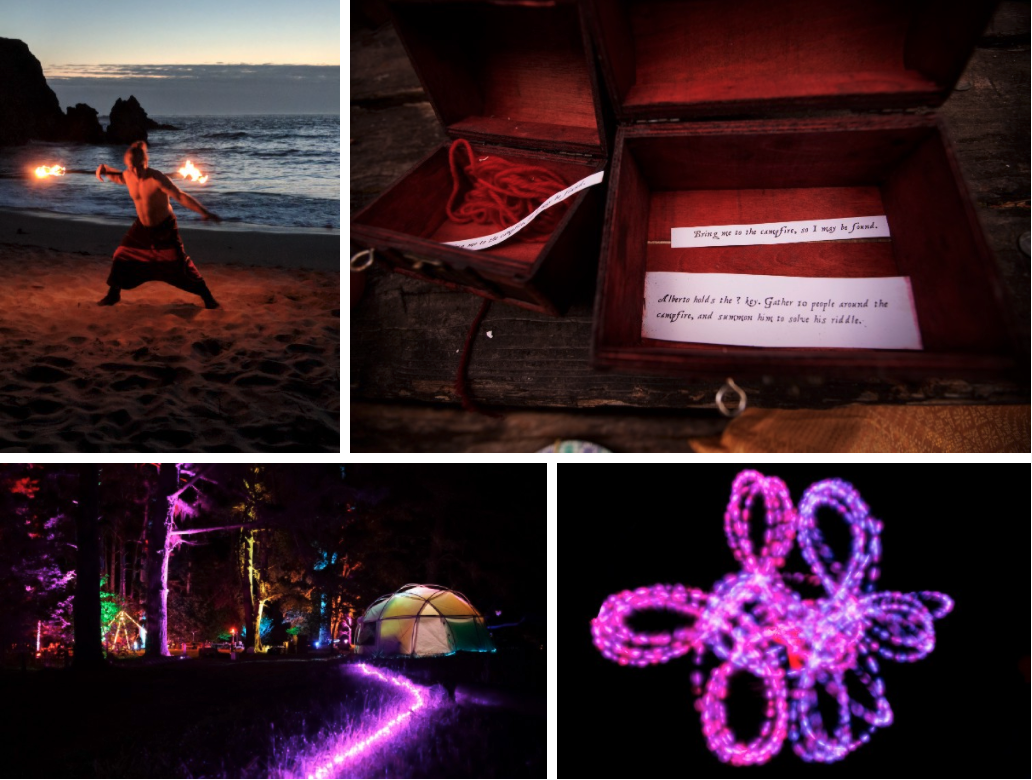

We chose to create two main gathering points — the farmhouse and the meadow, each with several connected areas that people could visit depending on their interests and mood. The farmhouse became the intellectual hub of the event — most of the workshops and talks were hosted there, and in the evening it became a space for conversation and music. It also had a teahouse in a nearby cabin, providing a small, more introverted space. The meadow became the more exuberant space. We lit it up with art and club lights at night, and it had a campfire, a dance area, and a burningman-style dome where people could give each other massages and snuggles. We set up bars and food tables in both areas to ensure that people didn’t have to travel far for sustenance.

The Journey:

We wanted to create an intense transformative group experience to help as many people as possible achieve the right mindset for the event. On the afternoon of the second day, shortly after we finished setting up, we had an experience facilitator lead us on a several-hour journey through the forest and onto the beach. It was part guided meditation, part playful activities, and part ritual designed to help us reflect on our connections and what we want out of life. This worked quite well at a size of 35 people, the number who were there on the first day to set up. We had an amazingly memorable time together, and many people mentioned coming to important realizations as a result of the journey. Looking back, this felt as important as the ceremony in terms of what will most cherish years from now.

The Ceremony:

We looked to have the ceremony not just celebrate and share our commitments to each other, but also act as a celebration for the biggest commitments we and others were making in our lives. This included commitments to ourselves, each other, our community, and the world.

For us, the institution of marriage is an active choice by a couple (or small group) to commit to building a life together. It’s something that’s not to be entered or left lightly, and it often involves making deep long-term emotional and financial commitments. As this partnership is core to our lives, we also look to our community to support us in this decision.

Our act of committing to each other happened the moment we decided to get married. We had been dating for four years, knew what each of us wanted out of a marriage, and knew we could trust each other at our word. By the time our wedding happened, our stated commitments were already commitments. However, it was still special to celebrate them in front of our friends as well as invite everyone to support us in achieving them.

We also used part of the ceremony to tell the story of our relationship, sharing both the excitements and the challenges we faced, noting that no relationship is a perfect straight line from love at first sight to marriage. The story of our relationship gave us a chance to acknowledge friends and family members who helped us along, and also set the context for some of the commitments we had made.

We both identify as spiritual but not religious, and our own personal spiritual philosophies are probably best described as a mix of secular humanism and transhumanism. We opened the ceremony with a presence meditation to get everyone focused on the present moment, and closed it with a reflection on the vast narrative of the cosmos awakening to self-awareness via sentient life, different paths this narrative could take, and the specialness of the current moment in time in deciding our collective fate.

We officiated our own ceremony. This felt like a natural decision to us as recognition of our union comes from ourselves first and our social group second. We only needed our promises to each other to make it official.

Script for the ceremony. We didn’t follow the script exactly, but we used it as a general guideline to keep ourselves on track.

Activities:

We encouraged people to give talks and host workshops on a wide range of topics throughout the weekend. Topics ranged from yoga to partner dancing to real estate investing to strategies for successfully finding a long term partner and building a life together.

The activities gave people another way of getting to know more about one another, and in many cases helped foster discussions around long term life planning.

We also had purely exuberant activities such as a late-night combined cello concert and light-painting workshop.

The activities were so popular that we ended up having three workshop tracks at the same time, giving everyone tough choices between all the options.

Art:

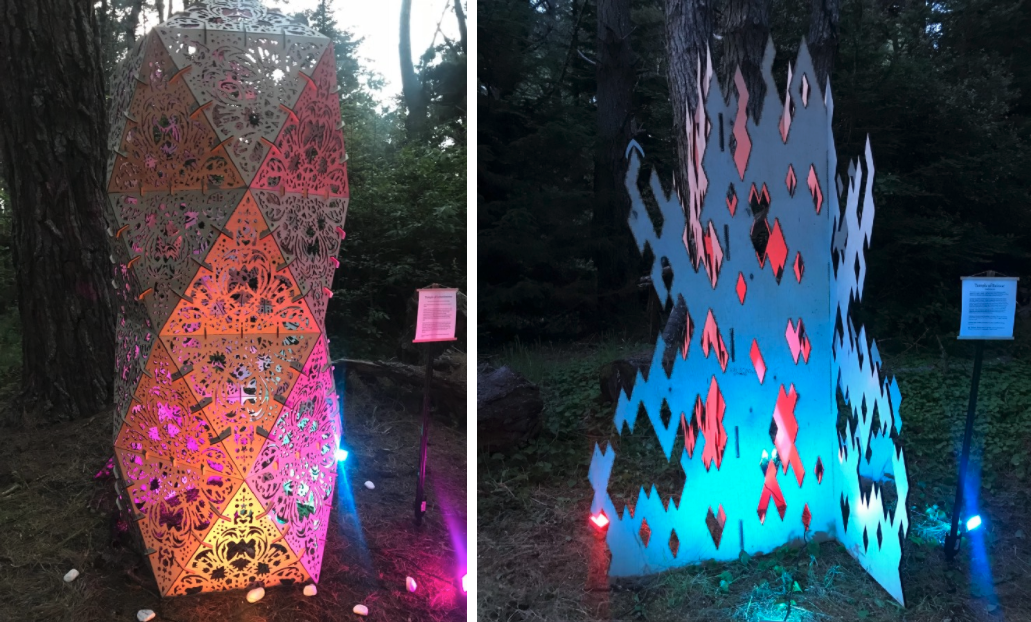

We encouraged people to create art that helped them on their own paths of intention-setting and commitment. A core group of us designed a pair of temples to act as a focal point. One was the Temple of Commitment, which invited people to write commitments they were setting for themselves on white stones and place them at the base of the temple. The other, the Temple of Release, gave people a place to write down parts of themselves that they are ready to let go of, whether they are regrets, sorrows, or other things weighing them down. People wrote directly onto the surface of this temple. Seeing the gathered anonymously written burdens of a large number of people in one single place was emotionally very powerful. On the final night, we burned the Temple of Release on the beach to symbolically release everyone’s regrets.

Money:

Our decision to focus the event on the deeper meaning of commitment and forego most of the visual trappings of weddings let us cut out the marriage-industrial complex almost entirely.

We wore beautiful clothing that cost us a couple of hundred dollars. What matters is wearing whatever you feel best commemorates the occasion as opposed to wearing the same style of white dress that Queen Victoria wore to her wedding in 1840, a particular style of white dress that now has drastically inflated prices and no other use after the wedding.

We chose to forego the purchase of wedding rings. Neither of us has a particular attachment to wearing a physical emblem of our union, and we don’t feel a strong desire to signal our status as married in most social settings. We particularly aren’t interested in rewarding De Beers for their century-long near-monopoly and marketing campaign to position diamonds as a luxury good.

For food, we got the costs down to <$10 to $15 per person for each meal by making very large orders at high quality local restaurants and doing some meals ourselves as a group. This was much more affordable than professional onsite caterers, which tend to be very staff-heavy operations that also charge a large premium for weddings. Additionally, breakfast catering never seems to work out all that well; with people eating breakfast across a broad range of hours, catering trays invariably end up containing a mix of dried-out bacon and eggs that have been heating in the tray for too long. Doing large-scale food preparation ourselves for 100+ people was less daunting than anticipated; each meal was split up into a handful of dishes that were easy to prepare at scale. Soups, salads, and sous-vide meats all scale well to very large amounts without requiring a lot of labor. One of the other great things about eating food prepared by your friends is that it’s another way to connect with them; you’re not just eating cookies, you’re eating special cookies that your friend made knowing your taste in cookies.

The wedding premium applies to cakes as well; as soon as a cake looks like a wedding cake, the prices go way up. On the other hand, bulk sheet cake orders from high end bakeries are surprisingly cheap; we were able to feed everyone multiple types of delicately flavored cake for about $3.50 a person.

Finally, a lot of the roles traditionally filled by outsiders (eg music, photography) were passions of people in the group. By having so many of these roles filled by people in our social group, it enhanced the feeling of the event as an act of community co-creation.

We did pay an event planner to be on duty for the entire event to keep things on track and ensure that any situations that required sustained serious attention could get dealt with. This was definitely a good idea.

Overall, despite the fact that the event lasted four days and had over 120 people present, we kept the costs well below what the typical American couple spends on their wedding.

Reflection:

It’s now a week after the event, and we’re still glowing from the experience! Getting to spend a long weekend with a large group of friends collectively affirming our connections to one another in a meaningful way was particularly incredible. We heard from people who told us they had personal revelations or had made relationship or career decisions at the event, as well as many others who had just had a particularly good time. This makes us incredibly happy — it’s exactly what we hoped would happen. We’re also deeply thankful for the many hours that so many people put into the event. It could not have happened without a large group effort.

We’re already excited to figure out how we’d like to make this a yearly occurrence. It will give us a chance to gather periodically as a group to reflect on where we are and where we’re going, and perhaps the next event will celebrate someone else’s marriage or another major landmark in their life!

If you are considering getting married, we strongly urge you to consider doing something like this, or at least question the standard assumptions about what a wedding should be. It took a good bit of planning to really think from first principles about what we wanted to create and then bring it into reality, but ultimately it was a particularly rewarding experience.

This post was originally published on Medium.