It’s summer! School’s out, and people are excited to travel! My wife and I have spent over two weeks on the road since the beginning of June, and we wanted to share about how you can have amazing adventures even if you’re very risk-averse and want to minimize your chance of catching COVID.

This is a US-centric guide. If you live in a part of the world that has successfully handled COVID, lucky you! You and your fellow citizens get to enjoy something approaching normalcy. However, if you live in the US and are frustrated that you did your part and diligently socially distanced for months while other people kept having house parties, but now you’re tired of this mess and want a vacation, this guide is for you.

We’ll answer basic questions like:

- Where to go

- How to evaluate COVID risks as you travel

- How to handle transportation, lodging, and meals safely

- What it’s like out there

WHERE TO GO:

COVID has significantly shifted the balance of what travel destinations are feasible and interesting. International travel is nearly impossible right now, with most of Asia, Europe, and other parts of the world saying “no thanks” to American visitors until we get our shit together. America is, generally speaking, being quarantined because it failed to fight the virus. The few exceptions are mostly tiny tropical island nations that are starving for tourist dollars. As America sees a second spike in cases, other countries may take further steps to cut themselves off from American visitors.

Separately, now is not the time to visit big cities or even small ones — the most important draws in these cities are generally shut down or likely to be soon. New York is a wonderful exuberant paradise of wonder and beauty during normal times, but it’s a shell of itself right now.

This makes now the perfect time for the Great American Roadtrip. America is vast and filled with beautiful scenery, from mountains to beaches to deserts, and it’s waiting for you.

One thing to consider when choosing destinations is the current level of COVID cases in the area you’re traveling to. Some areas have literally 100x the caseload of others. You can use this map and zoom in on whatever states you’re traveling to to see results at the county level. Make sure to select “last 7 days” to get a sense of how many people are likely currently infected, and “per 100k” to have a sense of per capita risk. Lassen County (the purple area in the upper right) had 500 cases per 100,000 residents in the last week, which means that roughly one in every 200 people has a known recent case of COVID, and even if those people are staying home, there’s probably an equivalent number walking around presymptomatic and contagious. Buying groceries at Safeway there? Statistically speaking, someone in the building probably has it.

The good news is that there’s a vast world of beautiful natural spaces out there. America is particularly blessed in this area, with the sort of world-class scenery that formerly drew people from other continents to tour. Right now, domestic tourism is a fraction of what it is normally and international tourism is almost non-existent. As a result, we had well-known monuments like the Devil’s Postpile to ourselves, and we had beautiful hikes all over the Sierras.

One challenge is that The Great Outdoors is only partially open. With limited staff and delays due to shelter-in-place for nonessential park employees, many national parks still have some roads and campgrounds closed, and you’ll have to check websites carefully to ensure that the hike you want to do is actually possible. Sometimes this works out well, and a scenic park road becomes temporarily bicycle-only, letting you have a lovely adventure zipping along a road that’s normally full of RVs and awkwardly swinging trailers.

HOW TO EVALUATE THE COVID RISK OF ANY ACTIVITY:

As you go on the road, you’ll have a long series of decisions to make about what activities are safe to do. I’ve seen a lot of guides floating around around the relative COVID risk of different activities, and very few of them either provide you a sense of true risk or give you the tools to perform evaluations on your own. I’d like to correct that by offering three levels of detail so you can pick the one that suits your tolerance for complexity.

Very simple version:

Want to just be told what to do? Get some good masks (N95 or better), always wear them if you’re indoors in a public space, don’t spend more than a few minutes indoors, and don’t go into confined, crowded spaces even with a mask. Wear at least a basic mask outdoors as well unless there’s literally no one around. Definitely don’t eat at restaurants or bars unless they have ample, well ventilated outdoor seating for you and are nowhere close to full. Bring hand sanitizer in a refillable pocket bottle everywhere you go, and sanitize your hands after any period of touching things in the public sphere (eg after going into a supermarket, pumping gas etc). Don’t touch your face in public.

Simple version:

Want a simple mental model for how the virus spreads? There are two ways COVID spreads — droplets and surfaces. Most of the spreading happens through droplets breathed out by an infected person and then breathed in by someone like you. Surface transmission is more rare but it can happen in some situations, for example if an infected person breathes onto a surface that you touch with your hand, and then you rub your nose with that hand, you may be transferring viral particles into your nasal passage.

We’ll talk primarily about droplet risk. When people breathe, they exhale droplets that can travel several feet before settling down to the ground, and may take anywhere from a couple of seconds to a few minutes to settle depending on the size of the droplets.

Here’s a very simple way to think about droplet risk: imagine that everyone else around you is smoking cigarettes continuously, exhaling a cloud of heavy cigarette smoke with every breath. How much smoke do you cumulatively breathe in over time? That’s a very rough model of your COVID risk. You might breathe a bit of smoke in hanging out on a park bench as other people walk by, but you’re going to breathe hundreds of times more smoke in if you’re hanging out at a rowdy bar. Thus, the bar is hundreds of times more dangerous, like walking into the reactor at Chernobyl.

Next, to think about surface risk, imagine that everyone is constantly breathing a fine mist of green paint that settles to the ground within a few feet of them. Furthermore, imagine that they have green paint on their hands that rubs off on anything they touch. Most common surfaces, like door handles, will have some green paint on them. This paint on surfaces will fade away over a few hours or days. It’s harmless to get the paint on your hands, but you want to make sure you don’t get any on your lips, nose, or eyes by touching your face with your hands. Thus, you’ll want to wash or sanitize your hands after any period of time that you spend touching surfaces with green paint on them. You probably don’t have to worry about many-hop transmission as much since the amount of green paint will decrease with each hop. For example, if someone else touches their pants and then sits in a chair, and then later you sit in the same chair, and then later you touch your pants, the amount of remaining green paint is probably very low.

Note that these models are vastly oversimplified, but they’re better than nothing.

The full model:

If you have a limited tolerance for complexity, feel free to skip to the next section. However, if you want a more detailed mental model, we’re here to help! This model is enough that you’ll be able to evaluate a wide variety of different activities yourself instead of relying on a guide. It should take only about 5 minutes to read, and it will equip you particularly well to make decisions.

The numbers I mention here are not exact, but they are my best estimates having done a lot of research into the efficacy of masks as well as other characteristics of how COVID spreads. If you want sources, you’ll find most of them in this post from a couple of months ago.

The factors to note with droplet risk are:

- Distance: If you’re just a couple of feet from someone, your droplet risk is many times higher (hard to estimate, but it might be 10x+ higher) than if you’re ~10 feet away

- Confined space: If you’re in a small room with poor ventilation, you’re far more likely to breathe in someone else’s exhaled air than if you’re outside. The difference here could be 10–50x.

- Length of time: If you spend an hour near someone, you’re far more likely to catch something from them than if you spend five minutes next to them. This might be roughly 10x higher.

- Crowding: Each additional person you’re near adds risk. Being near 10 other people is 10x more dangerous than being near one other person.

- Making noise: People who are talking, shouting, or singing are emitting far more droplets and with more velocity than people who are sitting quietly, on the order of 10x more. Think of speech as just another form of coughing.

- Masks: If you’re wearing a basic cloth or surgical mask, your risk is cut by maybe half. If you’re wearing a properly fitting N95 or better mask, you can cut your risk by 10x or more. If *everyone else* is properly wearing a mask, even a simple cloth one, they’re probably cutting your risk by 10x. That’s a bit of a curse; unless you have a good mask, you’re dependent on everyone else’s behavior.

- Baseline rate of infection (as talked about in the previous section): The chance that a given stranger has COVID. Based on household transmission data, we can estimate that sustained close contact with someone who had COVID gives you a 10–30% chance of catching COVID from them.

As an example, let’s compare sitting on a park bench with going to a rowdy bar. At the park, you’re outdoors, whereas at the bar you’re in a small confined space. At a park bench you may have a handful of other people standing ~10 feet away at any time. At the bar, you’ll have a lot more people, and they’ll be right next to you. Separately, suppose you wear a basic cloth mask at the park, but everyone else is not wearing a mask. At the bar, no one is wearing a mask. At the park, people will probably be talking, but probably not loudly. At the bar, people are shouting and making a lot of noise (and droplets). Thus, to compare the two activities, you get: distance (10x) * confined space (50x) * length of time (same) * crowding (5x because 5 times more people) * noise (2x for talking vs loud talking) * masks (2x) = a 10,000x difference in risk between hanging out at a park bench and hanging out at a rowdy bar.

While surface risk is not the main transmission vector, it’s worth paying attention to it as well. The virus takes anywhere from a few hours to a few days to fully decay on surfaces depending on the surface and whether there is sunlight shining on it (UV accelerates breakdown), and it does so on an exponential curve, so surfaces are most dangerous when someone has touched them or breathed on them very recently. Some surfaces also get touched or breathed on a lot more than others, so a door handle or credit card point-of-sale system is more dangerous than a can of soup on the top shelf in a grocery store. The best way to handle this is to be aware of any period of time that you spend touching a lot of public surfaces, and make sure that you don’t touch your face during this period and that you sanitize your hands at the end of this period.

One other point — there’s a difference between what patterns of activities are low-risk for you and what patterns of activities would still keep R under 1 even if everyone did them. Don’t go to an area with a low COVID caseload and act with abandon; that’s not how we get out of this crisis. You have to keep your own impact on the communities you travel through low so you’re not contributing to the problem, even if other people are.

TRANSPORTATION:

Are you driving your own car? Great. That’s your quarantine fortress, and it’s all yours. Don’t let anyone who isn’t in your group inside it, and it will be safe.

Renting a car? Someone else may have been in there vacuuming it (or even driving it) as recently as a few hours ago. To be on the safe side, you should use some disinfectant wipes or a bottle of isopropyl alcohol and some paper towels to wipe down all the commonly used surfaces (eg door handles, steering wheel, radio, ignition, keys, glove box). This takes just a few minutes. If you want to be extra careful, wear a mask for the first few minutes of using the car until the air has circulated out.

Flying? OK, it’s possible, but it’s not going to be easy.

If the equivalent drive would take 10 hours or less, you should just drive. However, it’s reasonable to consider flying as an alternative to a long cross-country drive. Five hours in an airplane can be very risky, but so is five days of grueling driving.

An airplane can have the same density as a crowded bar, and you spend a lot of time in the crowded metal tube with the other passengers. Ventilation is decently good for such a dense indoor space, but it’s not good compared to being outdoors. Airlines have reduced flights to meet reduced demand, so there’s some likelihood that your flight will be close to full. To make matters worse, many airlines no longer keep the middle seats open, so you could find yourself literally 2 feet from an unmasked stranger for several hours.

If you really have to fly, you need to commit to wearing a really good respirator and goggles for the entire flight. N95s are probably not sufficient. You should get yourself a P100. Worn properly, this cuts out 99.97% of small particles from the air you inhale. Note that wearing it properly involves shaving off your beard if you have one. As a side note, since these masks have an exhalation port, you’ll want to put a little strip of fabric over this port to filter the air you exhale so others don’t have to breathe your outbreaths.

Treating the airplane cabin as a high-risk area and wearing a P100 makes flying far safer than it would be otherwise.

Other things to consider to reduce risk:

- If you’re two people in a 3-person row, book the extra seat to keep it empty so you’re not next to a stranger

- Try to find a flight that’s as empty as possible, like a very early or a very late flight. (though there’s no guarantee that it won’t get filled with standbys)

- Try to get a direct flight so you spend fewer hours airborne and in airports.

- Although airports are relatively empty, avoid using the restrooms there as there’s a lot of surface risk as well as possible droplet risk from aerosolized feces). If you have to use the restroom, keep your mask on the whole time.

- Wear a thin hoodie that you can take off as soon as you arrive, ridding you of other people’s droplets that may have landed on you.

LODGING:

As in the distantly remembered world of 2019, you have multiple lodging options including camping, airbnbs, and motel / hotel rooms.

Camping:

Camping is a relatively easy way to keep safe. You control all the surfaces you sleep on, and campsites are regularly baked with sterilizing UV light every day, so the risk from prior campers is low. Unfortunately, many campgrounds are still closed, making the demand for campsites far outstrip the supply. This makes dispersed camping and backpacking an appealing option. Most national forests allow you to camp almost anywhere — you just have to be away from developed areas, at least 100 feet from any stream, and within 150 feet of the roadway, and make sure to leave no trace when you depart. Additional local rules (for example, around making fires) may apply.

One issue with camping in campgrounds — you may want to watch out for the restrooms. They are an area where a lot of people touch the same surfaces and, if they have flush toilets, they may be a place where contaminated fecal matter is getting aerosolized. Consequently, you’ll want to wear a mask and sanitize any surfaces you touch in the restroom. Better yet, bring your own portable camp toilet — they’re very cheap.

Airbnbs, motels, and hotels:

It’s possible to stay in a rented room without taking on too much risk. Here’s how:

As with the rental car, you’ll want to sanitize all the commonly touched surfaces upon arrival. This includes doorknobs, countertops, handles, light switches, bathroom fixtures, bed headboards etc. You probably don’t need to go overboard though — unless you plan on sticking your face in the couch cushions, you don’t need to sanitize the couch. For additional safety, you can bring your own sheets, bedding, pillows, and towels so that you’re not rubbing your face in a quilt that the hotel staff might have breathed on a couple of hours ago. You’ll also want to put a note on the door asking hotel staff to not do any housekeeping so that you’re the only people in the room during your period of stay.

If you’re doing an airbnb, make sure you get the whole house and don’t have to deal with a shared kitchen or bathroom. Speaking of airbnbs, they have the nice advantage that you can cook your own food.

EATING:

It is of course possible to prepare all your own food during the trip, avoiding the world of restaurants entirely. This is the safest option. However, if you choose get food from a restaurant, here are some ways of reducing risk:

There’s tremendous variation in the hygiene and COVID-consciousness of restaurants across the US. Some clearly have gone to great lengths to keep themselves and their customers safe, while others are still partying like it’s 2019. State health mandates are no guarantee of what actually happens in the kitchen. However, the single biggest thing you can do to keep yourself safe in terms of food is to not eat inside the restaurant. Being in close proximity to other talkative diners is very risky and is the main risk in eating out, as we’ve seen in many superspreader events.

Take-out is by far the safest option, though outdoor dining at a restaurant may be reasonably safe in some circumstances. If you choose to eat outdoors, make sure to pick an area with a lot of ventilation and preferably a steady breeze, and make sure you have a lot of room around you. Go after peak hours so it doesn’t fill up around you. However, dining at the restaurant is rarely necessary. It’s easy to get your food to go and then eat it at a picnic bench in a nearby public park.

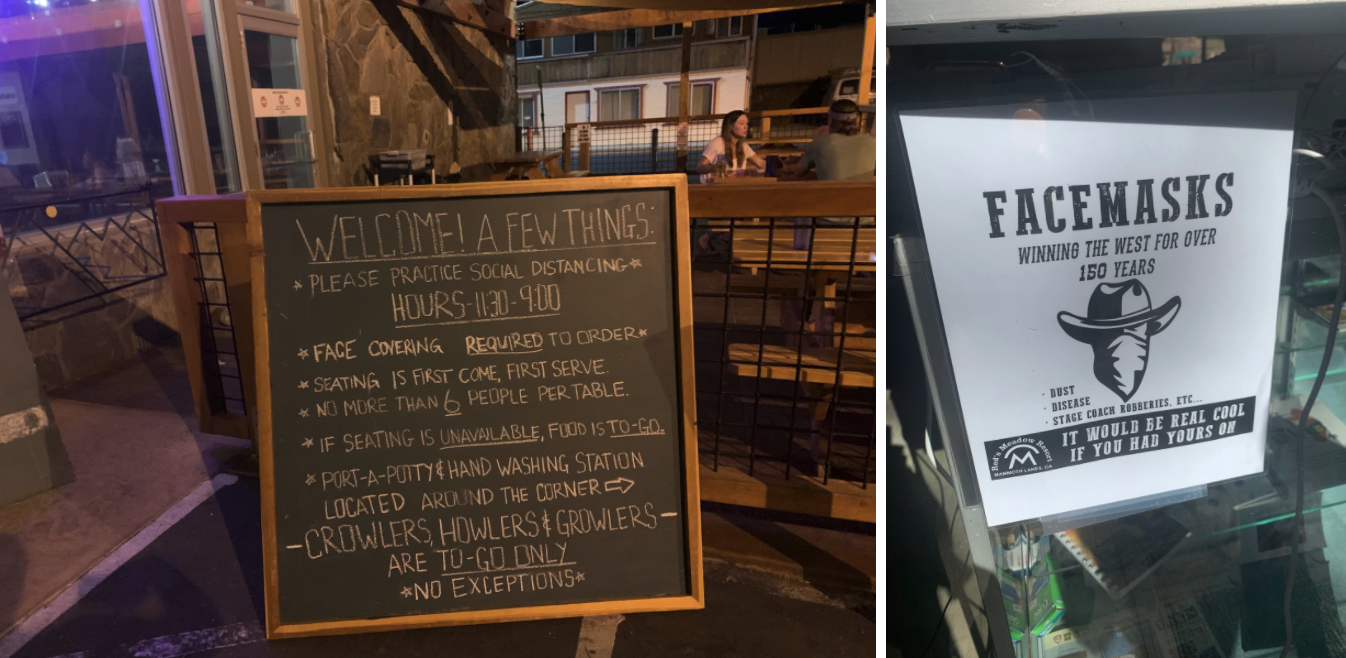

In terms of where to eat, you can usually get a sense of how conscientious the restaurant is around COVID by looking for commentary on their website or coming by in person and seeing how they’ve set their space up. If they have done things like post clear instructions about how to behave inside to reduce COVID spread, shield the cashier from you with a plexiglass sheet, or put the ordering table at the entrance so no customers go inside, it’s probably a good sign. You can also check the restaurant’s health inspector score on Yelp. It probably correlates reasonably well with how precautious they are about COVID.

If you walk in and see a dense line of people waiting to order and lots of customers without masks, it’s time to go find somewhere else to get your food. If you see the cashier pulling her mask down to rub her nose or talk, it’s time to go find somewhere else to get your food.

Asian restaurants are usually a good bet, especially if you’re doing an online order sight unseen. The people working there hail from countries that survived the SARS epidemic, and from what I’ve seen they on average take COVID more seriously than American restaurants. However, if it’s getting late and you’re in a rush, or you really just want a burger, In-N-Out has a very careful approach. At the three of their sites we visited, all their employees were wearing masks, even in Nevada where they are not legally required.

As you have probably heard by now, food containers pose some risk for COVID so you’ll want to open the container, sanitize your hands, and then eat while touching the outside of the container as little as possible.

OTHER ACTIVITIES

Many outdoor activities on shared equipment are quite safe (eg renting kayaks, bicycles, or jetskis). You may want to sanitize the equipment before use if it hasn’t been sitting in the sun, or sanitize your hands while using it.

Open-air outdoor museums are also quite safe, and many of them are open.

Beaches are reasonably safe if you stay physically distant from others and keep your mask on when you’re near other people. As we talked about earlier with our mental models for droplet spread, beaches have the advantage of being vast open-air spaces that are often windy, and that significantly lowers the risk. There has been a lot of criticism of crowded beaches as possible COVID spread points, but I think the risk is mainly from groups of people hanging out unmasked in close proximity and passing beers around. You can’t control other people’s behavior, but if you can get a bit of space for yourself and keep a mask on, you can be reasonably safe. In most cases, there’s plenty of room on the beach, and clickbaity articles about reopening beaches may have a more than a tinge of hype, as we see from this tweet about trick photography:

So don’t worry too much about beaches; in most cases you’ll be safe if you take reasonable precautions, and you might get to wear that nice new trikini.

On the practical end of things, pumping gas is quite safe so long as you sanitize your hands afterwards. Gas station bathrooms? Avoid them at all costs. They’re usually small and poorly ventilated.

In general, try to avoid using public restrooms due to the risk of aerosolized fecal matter. A lot of public restrooms will be closed in any case. It’s easy to bring a camp toilet or, if you’re in a sufficiently wild area, use the ecosystem’s ability to absorb organic matter. Buy a small plastic shovel so you can bury your poop.

SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Society’s infrastructure is slightly broken right now. Your airbnb is more likely to have something wrong with it. Restaurant staff are more likely to be confused and distracted by new procedures. Some roads will be closed. Some closed roads won’t be on the official map of closed roads. You’ll have to be patient and understand that the world of tourist infrastructure is also struggling to get things done under COVID restrictions and is a bit behind.

There are also significant cultural differences. You might walk into a supermarket and see that half the people in there aren’t wearing masks. You’ll have to decide if it’s worth shopping there. You’ll also run into the occasional person who will mock you for wearing a mask. You can ask if their parents are still alive, and then say “clearly you haven’t had a friend or relative die of COVID yet” and wait for the uncomfortable silence afterwards.

TRAVELING IN GROUPS

If you’re traveling with people outside your household / quaranteam, you will need to decide whether you stay physically distanced during the trip. This is a big topic, but if you decide to “merge” during the trip, have everyone avoid any undistanced social activity during the 10+ days prior to the trip to minimize the chance that people in the merged group get each other sick. Of course, if anyone’s feeling sick at all, they should stay home. If you don’t decide to merge, you’ll need to make sure everyone has their own car and place to stay, and you’ll also want to have a detailed conversation where you share your risk tolerances so that everyone’s on the same page.

SHOPPING LIST

Aside from the usual items you’d bring on a camping trip, here are some COVID-specific items that are useful to have:

- A set of N95 masks, preferably from a reputable manufacturer like 3M. They are usually sold out online, but you can find them at many smaller hardware stores if you call around.

- A P100 respirator and goggles if you’ll be flying.

- A set of more basic cloth or surgical masks for casual outdoor use.

- Isopropyl alcohol bottles + paper towels so you can sanitize surfaces. Alternately, you can get alcohol wipes, but you’ll go through them very quickly.

- A big bottle of hand sanitizer you can keep in your car.

- Small refillable bottles of hand sanitizer you can keep in your pocket at all times.

- A portable camp bucket-lid toilet so you can avoid public restrooms

- A small plastic backpacking shovel and toilet paper so you can bury your poop in the wilderness.

HAVE FUN!

A few people have asked us if it’s worth traveling at all given all this extra work. This seems like a silly question. COVID-prevention-related tasks add maybe half an hour of work per day at most, and the amount of time required goes down as the routines become automated. At the rate we’re going, it’s going to take a very long time for society to return to normal, and vacations are important for psychological health. Get out there and have an amazing time, and come back refreshed!

Originally published on Medium.